Never say No or Yes. Use the negotiated yes: "Yes, if…"

By Thomas Wood

At a workshop I recently conducted we had an interesting discussion regarding negotiation styles. Some of the participants said they were shy and wondered if this would affect their success as negotiators. They were surprised to learn my answer.

In my experience, some of the best negotiators are actually calm, laid-back and quiet. This often surprises people because they have an image of successful negotiators as being flamboyant, high-energy and somewhat colorful. That is typically true in the movies, but not necessary in real life.

The beauty of the Best Negotiating Practices (BNPs) we teach is that they fit every negotiation style and personality. As long as negotiators do their homework, start at their most desirable outcome (MDO), listen for the true interests of their counter-parts, and use the rest of the BNPs, they will usually have a satisfying outcome of mutual gain, no matter how shy or out-going they are.

Having said that, one might consider cultural differences when deciding what the most effective personality style of your lead negotiator should be. In some cultures, my out-going, energetic style will be welcomed, in other cultures it will backfire on me (more on cultures in a future blog). You should also consider the personality style of your counterpart when deciding who should be your lead negotiator.

At the end of the day though, everyone has the potential to become a master negotiator, no matter what personality style you have.

By Marianne Eby

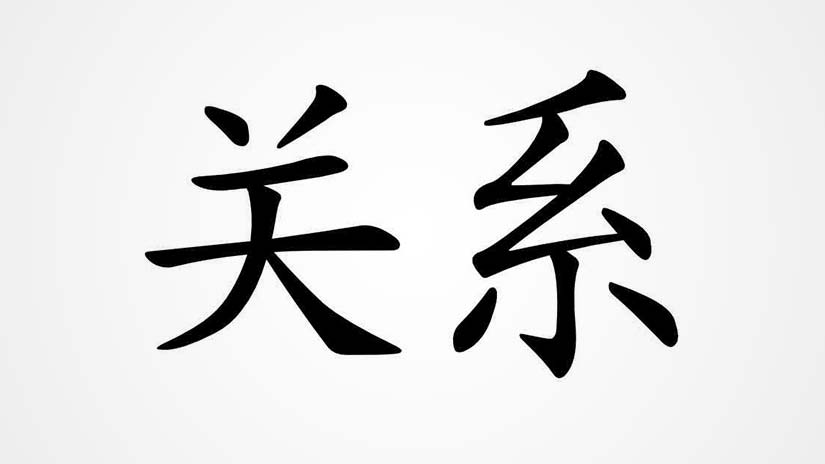

Our clients do extensive business in China, where negotiations tend to be a long involved process. What you thought would be a simple business negotiation often turns into multi-day affairs with many delicious meals, multiple toasts, and tours around the factory. While it takes time, this focus on Guanxi, which roughly translates to “relationships and connections,” is viewed as both effective and efficient in China. Good negotiators everywhere would do well to take a lesson and get in touch with their Guanxi.

The Chinese view their business relationships as cooperation amongst various parties that support each other towards mutual gain, where “business favors” or concessions are readily and voluntarily given, knowing that business partners would also be ready to give. Guanxi is a complex concept that involves respect, reciprocity, and a certain deference to the person with more authority, all in an effort to achieve a mutually beneficial relationship.

One famous story of Chinese relationship building is the story of Microsoft’s growth in China. Urban legend had it that on his first trip to China in the mid 1990s, Bill Gates insulted the Chinese President Jiang Zemin by wearing jeans and only leaving time for a brief visit. The legend had China’s President stating that Mr. Gates would be wise to learn more about Chinese culture, essentially saying that understanding China’s customs would pave the way for better working relationships in the country. This legend of course turned out to be pure myth and was later debunked in the 2006 book, Guanxi (The Art of Relationships): Microsoft, China, and Bill Gates’ Plan to Win the Road Ahead by Robert Buderi and Gregory T. Huang, which explored the success of Microsoft’s software laboratory in Beijing, China. The real story is that Gates and one of his key visionaries, Nathan Myhrvold, executed a strategy that set the company and the country on a long term course to build a mutually beneficial relationship by harnessing the talent from within China and learning the cultural knowledge necessary to be successful.

According to Buderi and Huang in Guanxi and the Art of Business, “So far, the company has invested well over $100 million and hired more than 400 of China’s best and brightest to turn the outpost into an important window on the future of computing and a training ground to uplift the state of Chinese computer science – creating dramatic payoffs for both Microsoft and its host country….” China is reaping the benefit of an elite corps of computer scientists, while Microsoft’s barriers to entry were eased.

The legend, the truth, and also the ultimate success of Microsoft in China demonstrate an important lesson: doing business requires understanding the culture of your counterparts and making an effort to build relationships in the ways that are important to them.

Negotiations in western cultures proceed at a speedy clip more often than not, but relative to the speed and cultural nuances, there is always a need to invest in the relationship. Building a strong connection up front with your supplier, customer or partners provides an invaluable foundation of trust and connection that supports all future negotiations in the relationship. Get in touch with your Guanxi!

By Thomas Wood

It may be months before you start trading concessions with your customer, supplier or business partner, but good negotiators know that every conversation preceding negotiations is an opportunity. With all eyes on Tim Cook, CEO of Apple Inc., as he follows in the footsteps of his legendary predecessor, Steve Jobs, we see a master negotiator who knows how to seize the opportunity to create value in negotiations that seemingly haven’t yet begun.

With September almost over and the school year in full swing comes the anxiety of grades, so we looked around to see who is likely to earn an A this year. We had to take note of how Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, handled his testimony before the US Congress at the start of this summer. Along with other Apple executives, Cook responded to a battery of questions from the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Tim Cook, who is still proving his mettle as the nation’s most famous succession CEO, ostensibly arrived on Capitol Hill to defend Apple’s corporate position on tax matters. He had not been invited to negotiate with Congress, but to be grilled about Apple’s use of tax loopholes. Yet, he used the opportunity to influence the negotiations that inevitably will unfold on this issue over the next few years.

Tim Cook deftly and proficiently demonstrated strategies consistent with Watershed Associates’ Best Negotiating Practices®. He reframed the issues to Apple’s advantage, was more prepared than his counterpart, and recognized and adjusted to his counterpart’s culture.

First, Cook used the opportunity of testifying to reframe the debate. Rather than solely responding and attempting to justify Apple’s corporate tax practices, Cook framed his corporate position based on the source of the rules. Cook accurately argued that Congress is the ultimate author of U. S. tax policy. Cook’s defense was primarily that Apple acted completely within the bounds of the law, and that Congress owns the authority and prerogative to change the law and its specifications. It’s the negotiator’s version of “don’t blame us when your lawyers wrote the clause!” Reframing this debate worked as an effective negotiating strategy so far for Apple, and caused Business Week and other news entities to declare that Cook “dominated” Congress.

Second, compared to some of the Congressional Committee members asking questions, Tim Cook appeared far more prepared. The vacuous nature of some of the “questions” posed, and fawning remarks delivered, to the Apple CEO is well documented. Cook’s answers, by contrast, were so deliberate and thoughtful that his extensive preparation for this appearance was made plain. The depth of Cook’s advance preparation was notable and widely observed in the Wall Street Journal's commentary. Similar to any business negotiation whether a mega-merger or spot buy, being more prepared gave Apple the upper hand that would not otherwise be easily retrieved down the road in the negotiation.

Finally, Cook seemed aware, and responsive to, distinct differences in culture between his organization—a massive, secretive, market-driven, successful for-profit corporation, and the comparatively dramatic, public and august entity that is the U. S. Senate. At Watershed Associates, we train clients about negotiating in contexts where there are definite cultural differences -- between corporate cultures, transnational or multinational. Our cross-cultural Safe-skills help businesses identify and assess distinctions in how their counterparts may operate, such as relationship v task orientations or collective v individual decision-making. Variances in style and strategy with regard to time, team hierarchy, and familiarity to name a few, are to be expected when negotiations take place across cultures. These variations need to be noted and appropriate adjustments incorporated into the negotiation plan.

Apple’s CEO recognized the most basic of these distinctions between cultures: formal versus informal hierarchies. Cook consistently (and perhaps insistently) referring to his Congressional interviewers very formally, as “Sir” and “Madam”. Conventions of address such as these are very rarely used in American corporate activity, and certainly not in the Jobs era of Apple. However, in other cultures—like the US Congress, but also in other countries—formal address is expected and is an effective signal of respect for the negotiation process and the negotiation counterpart. Apple corporate executives are unlikely to use these modes of address in any of their daily business, but in the business of negotiating with the Senate Subcommittee, Tim Cook acknowledged this cultural variance, and acted in a way that captured value for Apple’s objectives.

Although Tim Cook probably has years to go before he can be measured against his legendary predecessor, after Mr. Cook’s performance in front of the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, he brought Apple’s corporate practices through unscathed, and for the moment, unchanged. By reframing the debate, preparing extensively, and honoring the differences in organizational cultures, Mr. Cook led Apple with supreme effectiveness. Apple and its leader earned a Negotiator’s “A”.

By Thomas Wood

On World Food Day, October 16, 2015, will you be drinking China’s famous Huiyuan fruit juice or the iconic Coca-Cola?

At Expo Milano 2015, which closes this month, each showcased brand proudly stands alone as a key player in the planet's food. Not so long ago, however, the two companies were on the road to a blissful acquisition of China Huiyuan Juice Company by Coca-Cola. What happened to the deal, and what can we learn from the failed negotiations of these beverage giants?

Expo Milano 2015 offers a “platform for the exchange of ideas and shared solutions, stimulating each country’s creativity and promoting innovation for a sustainable future.” This sounds like a phrase out of our negotiator’s playbook! But Expo Milano of course is about food and its sustainability on our planet.

Coca-Cola is the Official Soft Drink Partner of Expo Milano. Huiyuan, China's largest juice manufacturer, is Expo Milano's Official Partner in the beverage fruits, legumes and spices cluster. It seems fitting that these two beverage giants each hold their own at the world’s food exposition, but I am reminded of an “almost event” in 2009, when the two were in talks for Coke to acquire Huiyuan as part of Coke's expansion in China -- a negotiation of shared ideas and solutions.

To Coke executives, the deal seemed like a perfect match. With 35 existing factories in China at the time, producing everything from soft drinks to milk tea, Coke had a long tradition of succeeding in the local market. After many negotiations, executives at Huiyuan had agreed to the deal, which led Coke to announce plans to commit an additional $2 billion to its presence in China over the next three years. Coke officials had proceeded adeptly from the start by investing time and energy into building relationships with executives at Huiyuan, as evidenced by the Chinese company’s major shareholders endorsing the merger. The business world was shocked when just a few weeks later, the Chinese government blocked Coca-Cola’s proposed $2.3 billion acquisition of Huiyuan in March 2009.

What scuttled the deal? Why had Coca-Cola been caught by surprise? The answer lies in Coke’s fundamental miscalculation of critical stakeholders’ interests – the Chinese government as the ultimate regulator of business in China, and the Chinese consumer.

Although the deal made financial sense for the two companies – one source close to Coca-Cola described it as a "marriage made in heaven,” regulatory officials in Beijing were looking at more than the bottom line. By 2009, Huiyuan had become a high-profile national brand, and its proposed sale to a US multinational had aroused tremendous opposition in local media outlets and online chat rooms.

Huiyuan’s founder and CEO also set off a firestorm after declaring that he was “selling [the company] like a pig,” with more than 80% of respondents opposing the deal on Xinhua, China’s state-owned news agency. With public sentiment turning increasingly against the deal, Beijing’s Ministry of Commerce felt comfortable and even empowered to scuttle the merger.

Beijing’s official rationale was that the deal would reduce competition. Many analysts observed, however, that Chinese officials simply believed that the public relations impact of approving the deal wasn’t positive enough to overcome the downside of creating an exception to China’s new anti-monopoly policy. No deal was therefore a better option than a deal that could be portrayed as a symbolic defeat for Chinese business. And therein lies the stakeholders' real interests: national pride in Chinese industry. No deal was sustainable if it didn't address these key stakeholders' interests.

Given its experience in the Chinese market, certainly Coke officials knew of the possibility that the Ministry would reject the deal. Coke probably did not expect, however, that Beijing would give in to public opinion and forego Coke's promised expansion in China. Coke may even have been blinded by its amicable relationships with Chinese companies.

What could Coca-Cola have done differently?

Coke’s negotiating team should have focused more on Huiyuan’s stakeholders – all of them, not just inside Huiyuan as its negotiating partner. Stakeholders who aren't at the bargaining table can crash the best-laid plans. Coke’s negotiating team could have brainstormed ways to adjust its offer in light of Beijing’s constituents’ reactions. Coke could have designed a campaign that would embolden Chinese national pride in the Huiyuan brand, rather than discourage it. It is difficult to believe there wasn’t a way to structure the deal that might have assuaged the public outcry, and even bolstered Chinese national pride.

Although Coke had developed close ties with Huiyuan officials, it was still at the mercy of the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. Earlier efforts to learn what would matter to the Ministry of Commerce on this front may have helped Coke succeed – or at least could have helped it avoid an expensive and time-consuming acquisition strategy that ultimately proved futile. And here we are 6 years later, with two strong beverage giants on the world food stage. Be sure to visit them at Expo Milano 2015.

By

Only a short time ago, business across Asia was booming. It is common knowledge that companies worldwide are dependent on Asian factories, and that the current pandemic is having a far-reaching impact on global supply chains.

Re-negotiating business deals with Asian counterparts will mean remembering your foundation lesson in cross-cultural negotiating. Here are some tips to help you wade through the negotiation process and emerge more likely to succeed.

Be aware of the decision-making process and authority

The decision-making process and authority can vary by culture — and this is important to take note of as it affects how long negotiations can take and who you need to convince. In general, Asian cultures typically have top-down or consensus-driven decision-making styles. For instance, while it may take US or German business days or weeks to make a big business decision from executives, research from the University of Hong Kong has found that the Japanese take weeks or months due to consensus-driven decisions, but can pay off with fast and smooth transitions once the decision is made. Additionally, recognition of seniority or hierarchy is also another aspect to pay attention to, as in Vietnam, you must show the eldest person respect by giving them your business card first.

Address communication gaps

Aside from having language barriers, sometimes the true meaning can get lost because of cultural mores that impact cross-cultural negotiations. For instance, most Chinese and Japanese  negotiators will never directly tell you “no”, but will expect you to understand it in other ways. This is also similar in India, where business negotiators have difficulty saying "no" as it can convey an offensive message, so they too, will say statements like "We'll see" or "Maybe" when they likely mean "No". For you to understand this, you must be able to distinguish high context and low context cultures. Blog on Linguistics defines the former as a culture where the context of the situation is emphasized, while the latter is a culture that emphasizes the verbal content of the message. In other words, high-context cultures are not straightforward, while low-context cultures are more straightforward. Realizing there can be gaps as simple as whether the word “No” was used or meant will remind you to seek clarification more often. Sharpen your skills with our tips for direct and indirect negotiators.

negotiators will never directly tell you “no”, but will expect you to understand it in other ways. This is also similar in India, where business negotiators have difficulty saying "no" as it can convey an offensive message, so they too, will say statements like "We'll see" or "Maybe" when they likely mean "No". For you to understand this, you must be able to distinguish high context and low context cultures. Blog on Linguistics defines the former as a culture where the context of the situation is emphasized, while the latter is a culture that emphasizes the verbal content of the message. In other words, high-context cultures are not straightforward, while low-context cultures are more straightforward. Realizing there can be gaps as simple as whether the word “No” was used or meant will remind you to seek clarification more often. Sharpen your skills with our tips for direct and indirect negotiators.

Allow them to Save Face

The West is highly individualistic compared to Asia. And while an article by Marcus on social media points out that we too are concerned about how others think of us, as “we might pick cars, accessories, clothes, and other material possessions based on what we believe these objects say about who we are,” the concept of ‘face’ is quite different in Asia. The Asian concept of ‘face’ is described as a combination of social standing, reputation, influence, dignity, and honor, and this is why East Asian cultures emphasize the importance of social harmony. For instance, you will not see a Vietnamese or Chinese businessperson pointing out that their boss made a mistake, as it makes the boss lose face because they were wrong, and the employee will lose face because they appear disrespectful. Understanding this delicate and respectful balance will help you maintain harmonious relationships when conducting negotiations.

Don’t assume their style of expression means the same as yours

When communicating with different cultures, how the other party views expression in emotion in the business setting varies to save face (see above). For instance, some cultures, such as the Chinese or Japanese, value a reserved style of expression and emotions, as well as seeing any public display as inappropriate. On the other hand, business culture in countries like India favors high communication, expressive styles, and value emotion as part of the process. They also appreciate humility and honesty even if things go wrong, as they are happy to guide you. Understanding this will help you avoid the trap of misinterpreting a reserved or expressive style during negotiations.

Aim for equally-mutual positive outcomes

Business negotiations in Asia are an opportunity to build relationships and find common ground. Uncovering mutual goals is vital for the parties to reach a win-win solution. Research from Singapore Management University suggests that Asian culture is fundamentally a low-trust culture, and will not do business with companies who they feel will not equally give and take. Thus, sharing the alignment of goals and aiming for mutually beneficial arrangements is vital to build trust, as companies are more likely to appreciate and build a long-term relationship with you if they see you are giving to the relationship in equal measure.

Take your time

Western cultures tend to view negotiations as sprints — the faster you get it done, the better. For Asian cultures, however, it’s better to take your time. It can take a lot of time for Asian hierarchy to make a decision, so Westerners need patience. For example, some Chinese and Indonesian businesses prefer to have ‘marathon-like negotiations,’ which means that most negotiations will occur over a long period of time. Not to mention, in the US, negotiations over the phone often happen, while some Asian cultures put a lot of emphasis on face-to-face interactions, regardless of how far away the two negotiators are from each other. In Singapore or Vietnam, for instance, meeting someone for the first time should occur in person, and be scheduled at least two weeks in advance. This is because they want to know who they're meeting, their role, accomplishments, etc. ahead of time. See our tips for building in time and showing patience.

by Farrah Prince

For the exclusive use of WatershedAssociates.com

Please provide us with some details and we will be in touch soon!